Reading an ingredients label can get confusing quickly. Some brands describe the same ingredient using different names, such as it's botanical name. Label formats, dosage levels and the level of detail provided per ingredient are additional variables. This can make a like for like comparison between products challenging.

At vital.ly we have started to standardise some things like naming conventions, to help make such comparisons easier. This post is intended to clarify some of the details around the legislative frameworks governing ingredient labels, and how these frameworks are applied to the labels on your favourite products.

Australian regulations - an overview

In Australia, food and medicines are regulated under separate legislative frameworks, corresponding with the intended use and potential risks those products pose to public health and safety. Within the regulatory frameworks, there are different requirements for foods and medicines in relation to their manufacturing, labeling, advertising, and evidence required to substantiate any claims made for the products (1). Let's walk through some of the basics including:

- Practitioner only products (and what makes them different to retail supplements)

- AUST L and AUST R numbers

- Ingredients list vs nutrition panels

- Herbal ingredients listings

- Equivalent values in ingredient listing

Products that are classed as therapeutic goods (which include prescription and complementary medicines) are regulated by the Therapeutic Goods Association (TGA) at a federal level while foods (including many that make health claims) are predominantly regulated by state and territory regulatory bodies (8).

State and territory food agencies regulate food in accordance with both state/territory and national food legislation, including food standards set by statutory body Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).

A product is classified as a medicine if it is represented to be a therapeutic good, likely to be taken for therapeutic use, or declared to be a therapeutic good. The TGA regulates medicines at the federal level (9).

Tablets, capsules, and pills generally provide a concentrated version of an ingredient compared to forms traditionally associated with foods, such as powders or bars. The manufacturing requirements for foods are not as stringent as for therapeutic goods (which need to adhere to good manufacturing principles (GMP) (1).

Table 1. Key differences between foods and medicines

|

|

Food |

Medicine |

|

Regulatory body |

FSANZ is the Commonwealth statutory authority responsible for developing food standards that make up the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code, which is enforced by the states and territories regulating the sale and supply of food. The Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code lists safety, composition and labeling requirements made on food labels and in product advertising. The Code regulates the use of ingredients, processing aids, colourings, additives, vitamins, and minerals (2). |

The TGA regulates medicines under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989. These include medicinal products containing herbs, vitamins, minerals, nutritional supplements, homoeopathic and certain aromatherapy preparations, which are referred to as 'Complementary Medicines’ (4). Complementary medicine means a therapeutic good consisting wholly or principally of 1 or more designated active ingredients, each of which has a clearly established identity and a traditional use (5). Australia has a three-tiered system for the regulation of medicines, which is overseen by the TGA:

|

|

Claims |

All health claims are now required to be supported by scientific evidence, whether they are pre-approved by FSANZ or self-substantiated (3).

General level claims refer to a relationship between particular nutrients or substances in a food, and their effect on health such as ‘calcium for healthy bones and teeth’. General level health claims are prohibited from referring to a serious disease or biomarker of a serious disease. There are currently a total of 201 pre-approved general level health claims available for use by food businesses across 39 categories. High level claims refer to a relationship between particular nutrients or substances and a serious disease or biomarker such as ‘Phytosterols may reduce blood cholesterol’. High-level health claims must be based on one of 13 pre-approved FSANZ health claims, across 10 categories. |

Medicines must meet evidence requirements proportionate to their health claims. |

|

Manufacturing |

Produced according to food safety standards. |

Medicines, including complementary medicines, must be manufactured according to Good Manufacturing practice (GMP). This set of principles and procedures ensure that therapeutic goods are of high quality (7). |

|

Labeling |

Need to include nutrition information (10). |

Medicine labels including complementary medicines, must display the active ingredient (6). |

|

Examples |

Energy drinks, cereal products. nutritional bars, meal replacement shakes. |

|

|

Availability |

|

Medicines have tighter regulatory restrictions than foods on where and how they can be sold and who can access them. |

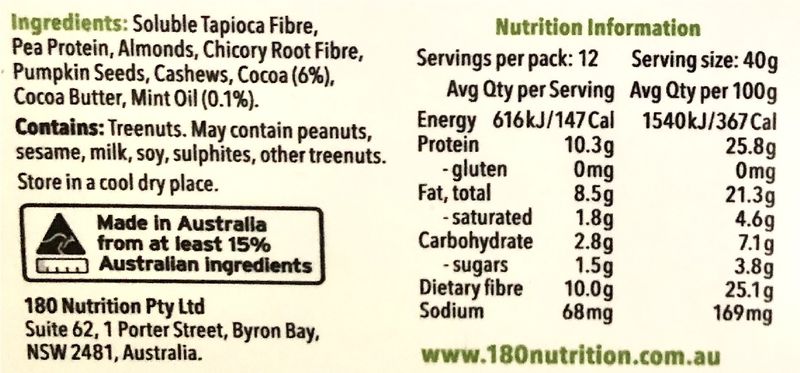

Figure 1. Example of food label (e.g. 180 Nutrition Vegan Protein Bars)

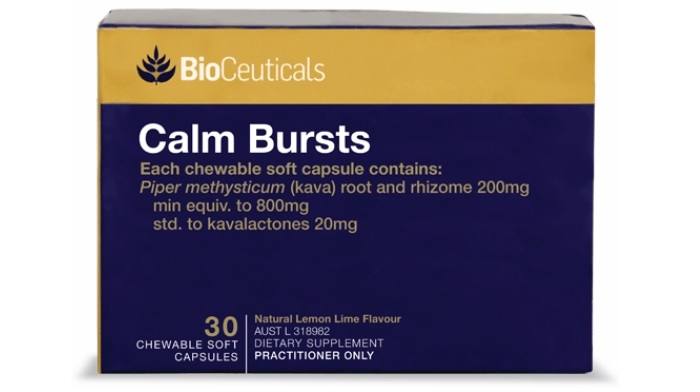

Figure 2. Example of complementary medicine label (e.g. BioCeuticals Calm Bursts)

Listed medicines – AUST L (e.g. Metagenics AdrenoTone)

'AUST L' medicines contain pre-approved low-risk ingredients.

Most complementary medicines are ‘listed’ with products clearly marked with a unique AUST L number. They are classified as unscheduled medicines with well-known, low-risk ingredients, usually with a long history of use, such as vitamin and mineral products. The TGA assesses such products for quality and safety but not efficacy. This is not an indication that they do not work, rather that the suppliers hold the evidence to support TGA indications ![]() and claims made for their medicine (11).

and claims made for their medicine (11).

Assessed listed medicine – AUST L(A) (e.g. Hydralyte Effervescent Electrolyte Tablets)

'AUST L(A)' assessed listed medicines may only use low-risk ingredients permitted for use in listed medicines. They must have at least one intermediate indication (i.e. indications that are above those available for AUST L listed medicines), and may also include lower-level indications. Assessed listed medicines have an AUST L(A) number on their medicine label (11).

Registered medicines – AUST R (e.g. Nurofen liquid capsules)

AUST R medicines are assessed by the TGA for safety, quality and effectiveness. They include prescription-only medicines and some over-the-counter products such as those for colds and pain relief (11).

AUST R registered complementary medicines are considered to be relatively higher risk than listed medicines, based on the ingredients they contain or the indications made for the medicine. All registered medicines are fully assessed by the TGA for quality, safety and efficacy prior to being available in the Australian market. Registered medicines have an AUST R number on the medicine’s label.

Therapeutic goods that are labeled for ‘practitioner dispensing only’ or words to that effect, are only to be supplied to and dispensed by a healthcare professional as described in section 42AA of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989.

The difference between ‘for practitioner dispensing only’ products and other listed or registered complementary medicines, is that the former does not need to include a statement of their purpose/therapeutic indication on the label. These medicines should only be supplied to an individual after consultation with a healthcare practitioner, at which time, the healthcare practitioner attaches a label to the medicine providing individualised instructions for use (5).

Health professionals who are found to be in breach of supply conditions may be subject to a voluntary restriction of supply. This a commercial decision made by suppliers of complementary medicine products, a practice which the TGA supports. This aims to ensure only qualified health professionals are supplied practitioner only products.

The TGA recognises the following healthcare practitioners (12):

- Medical practitioners, psychologists, dentists, pharmacists, optometrists, chiropractors, physiotherapists, nurses, midwives, dental hygienists, dental prosthetists, dental therapists or osteopaths; or

- Herbalists, homoeopathic practitioners, naturopaths, nutritionists, practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine or podiatrists registered under a law of a State or Territory.

Exempt goods

Some medicines do not need to be registered or listed on the ARTG as a result of a specific exemption or determination under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989. These include (13):

- Medicines (excluding those used for gene therapy) that are extemporaneously compounded or dispensed by a practitioner for use by a particular person

- Certain homoeopathic preparations

- Certain shampoos for the treatment/prevention of dandruff

- Starting materials used in the manufacture of therapeutic goods, except when formulated as a dosage form or pre-packaged for supply for other therapeutic purposes

Ingredients list vs nutrition panels

Sometimes confusion arises over the presentation of ingredients contained in a product compared to nutrition panel values listed for the product.

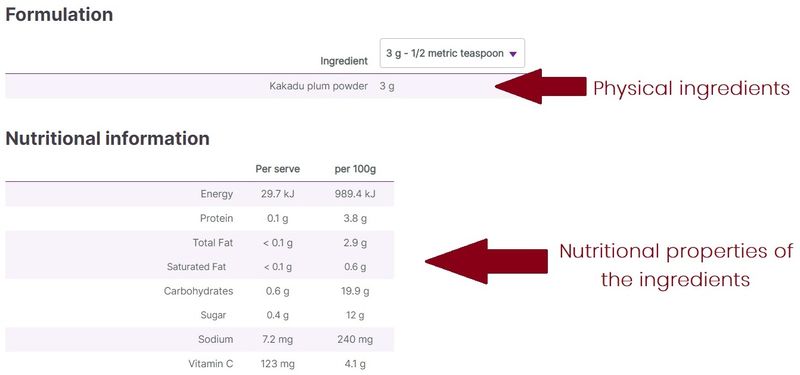

In general, an ingredient is a physical item that has been added to make up the product, whereas the nutrition panel displays properties of the ingredients. Nutrition panels typically contain the macronutrient content of the product (protein, carbohydrate, including sugars, and fat content), as well as other commonly used values when assessing the nutritional qualities of a product (e.g. sodium or fibre content). In addition, other properties of the ingredients might be listed, e.g. vitamin or mineral content.

For example, a product might contain orange juice, which by its nature contains vitamin C. The ingredient in this instance is the orange juice, whereas the vitamin C is a nutritional value of the ingredient, which might be listed on the nutrition panel.

In instances where the product contains vitamin C as an ingredient (usually synthetic vitamin C added to supplements), this is listed, with its amount, under ingredients. In order to compare vitamin C content with other products that do not explicitly have vitamin C added as an ingredient, the nutrition panel values can be useful.

At vital.ly, the difference between the ingredients and nutrition panel info is clearly displayed under different headings (Formulation/Nutritional information).

Figure 3. Ingredients vs nutrition panel data (e.g. GelPro Kakadu Plum Powder)

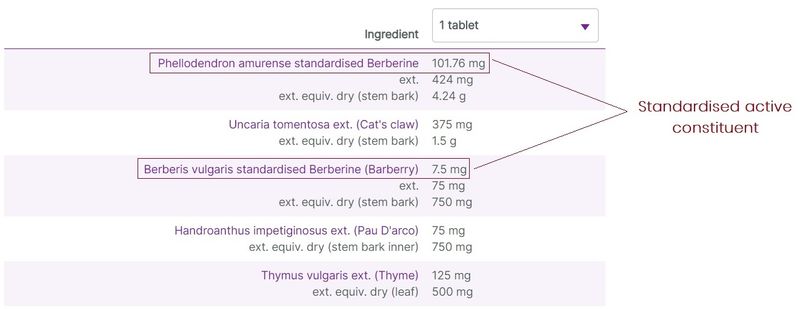

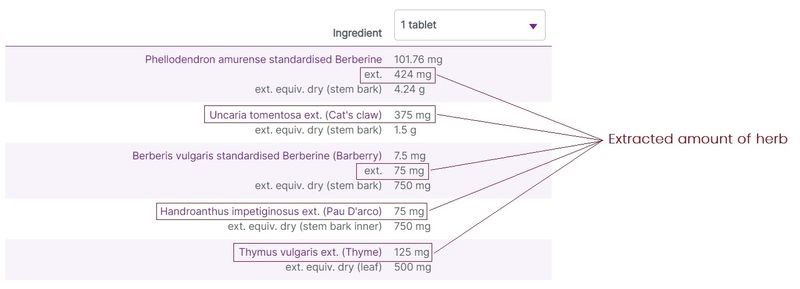

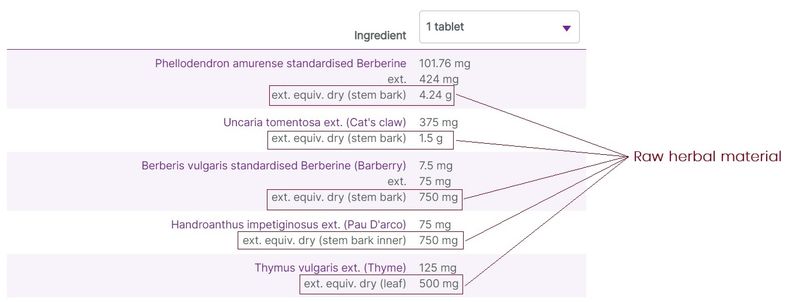

Herbal ingredients are most commonly listed on labels with varying degree of detail and amounts relating to the raw herbal material used in the preparations, and the extracted herbal components. At vital.ly, we standardise the ingredients listings to make it easier to compare products.

Typically, 3 levels of herbal detail are given (where the information is available):

- The original herbal content, including the part of the plant used. This is the raw material/content used to produce the herbal extract.

- The amount of the herb extracted from the raw materials. This is shown as the “ext.” amount.

- When a product contains information relating to the active constituents of the herbal extract, these are listed as “standardised” amounts. Where this information is available, it is displayed first for the ingredient listing.

Figure 4. Three levels of herbal ingredients data on display (e.g. Herbs of Gold Berberine-ImmunoPlex)

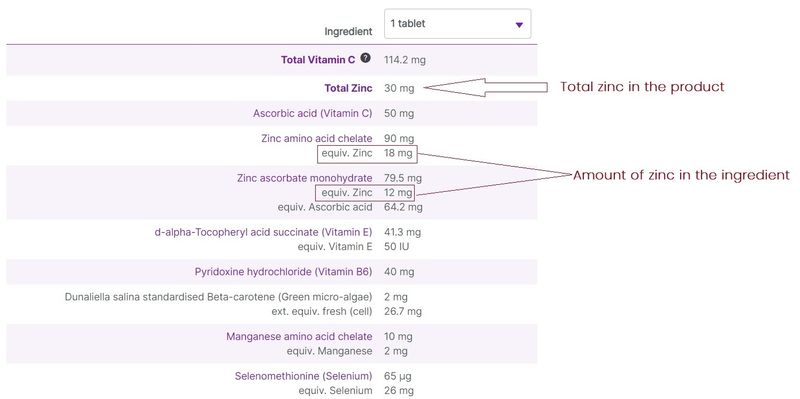

Equivalent values in ingredient listing

Some vitamin and mineral ingredients also contain active constituents. In these cases, the ingredient is listed, with the active ingredient given as an “equivalent” value. For example, a zinc amino acid chelate ingredient of 100 mg might contain 10 mg of zinc. At vital.ly, we have standardised the entry of the ingredients, making it easier to compare the amounts of vitamins and minerals in products, by displaying the equivalent amounts of these ingredients where they are available.

Figure 5. Equivalent values for ingredient listing (e.g. Eagle Zinc Zenith Plus)